Is It Good or Bad News If We Depopulate "After the Spike"?

Description

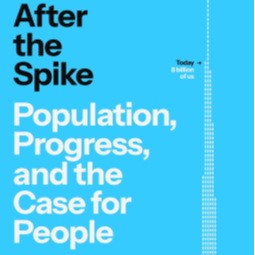

Simon & Schuster provided me with an advanced copy of the superb book After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People, scheduled for release on July 8, 2025.

The University of Texas authors, Dean Spears and Michael Geruso, have written a mind-blowing book! It's my second favorite book of 2025! My favorite 2025 book is They're Not Gaslighting You.

Video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-JfpjJRkok

Podcast

The Population Whimper

When I was born, Paul R. Ehrlich's book, The Population Bomb, was a mega-bestseller. Although I never read the book, my generation believed the book's message that humanity is dangerously overpopulated. The book gave me one major reason not to have children. The book made intuitive sense, built on Thomas Malthus's observations, that if our population continues to expand, we will eventually hit a brick wall.

However, Ehrlich, a Stanford biologist, made these stunningly wrong predictions in The Population Bomb:

- Mass Starvation in the 1970s and 1980s: The book opened with the statement, "The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now."

- England's Demise by 2000: He suggested that England would not exist by the year 2000 due to environmental collapse related to overpopulation.

- Devastation of Fish Populations by 1990: He predicted that all significant animal life in the sea would be extinct by 1990, and large areas of coastline would need to be evacuated due to the stench of dead fish.

- India's Famine: He predicted catastrophic food shortages in India in the 1990s that did not materialize.

- United States Food Rationing by 1984: He envisioned the U.S. rationing food by 1984.

Instead of all this doom and gloom, here's what happened: we went from 3.5 billion (when Ehrich wrote his doomsday book) to 8 billion people today, most of whom are fat. Today, our biggest problem isn't famine but obesity.

Dean Spears and Michael Geruso's new book should have been called The Population Whimper because it says the opposite of what The Population Bomb said. Forget a catastrophic demographic explosion. We're going to suffer a catastrophic demographic implosion.

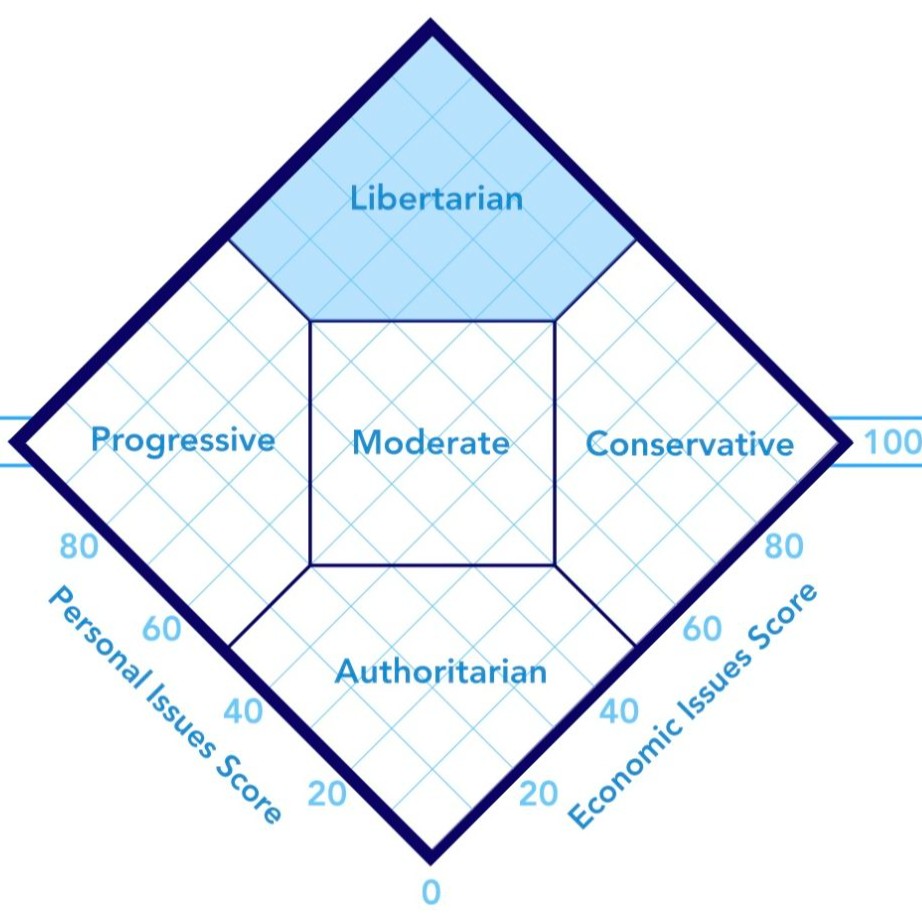

The graph on the cover of After the Spike sums up the problem: during a 200-year time period, the human population will have spiked to 10 billion and then experienced an equally dramatic fall.

Three criticisms of After the Spike

For a book packed with counterintuitive arguments, it's remarkable that I can only spot three flaws. Admittedly, these are minor critiques, as they will disappear if we stabilize below 10 billion.

1. Wildlife lost

The authors correctly argue that the environment has been improving even as the human population has been growing rapidly. For example:

- Air and water are now cleaner than they were 50 years ago, when the population was half its current size.

- Our per capita CO2 consumption is falling.

- Clean energy production is at an all-time high.

There's one metric that authors overlooked: wildlife.

As the human population doubled, we've needed more space for growing food. This has led to a decrease in habitat, which is why biologists refer to the Anthropocene Extinction.

- While fish farms are efficient, overfishing continues.

- The Amazon gets denuded to make space for soy and cattle plantations.

- The loss of African wildlife habitats is acute, as the African population is projected to quadruple in this century.

I imagine that the authors of After the Spike would counter:

- National parks didn't exist 200 years ago.

- Green revolutions and GMO foods have made the most productive farmers ever.

- De-extinction may restore extinct species.

And they're correct. There are bright spots.

However, as we approach 10 billion, wildlife will continue to suffer and be marginalized. The book should have mentioned that.

Dean Spears and Michael Geruso would likely agree that if humans continue to grow nonstop, wildlife will continue to suffer.

However, they aren't arguing for nonstop human expansion. They want stabilization.

When you combine stabilization with technology (e.g., vertical farming and lab-grown animal products), we would reverse the downward trend in wildlife habitat.

2. Increased energy consumption

Dean Spears and Michael Geruso celebrate humanity's progress in energy efficiency and productivity. However, they overlook these facts:

1. The Rebound Effect (Jevons Paradox):

As energy efficiency improves, the cost of using energy services effectively decreases. This can lead to:

- Increased usage of existing services: For example, more efficient air conditioners might lead people to cool their homes to lower temperatures or for longer periods. More fuel-efficient cars might encourage more driving.

- Adoption of new energy-intensive activities: The increased affordability of energy services can enable entirely new consumption patterns that were previously too expensive to adopt. Think about the proliferation of data centers for AI and digital services, or the growth of electric vehicles. While individual electric vehicles (EVs) are more efficient than gasoline cars, the rapid increase in their adoption contributes to overall electricity demand.

2. Economic Growth and Rising Living Standards:

- Increased demand for energy services: As economies grow and incomes rise, people generally desire greater comfort, convenience, and a wider range of goods and services. This translates to greater demand for heating and cooling, larger homes, more personal transportation, more manufactured goods, and more leisure activities, all of which require energy.

- Industrialization and urbanization: Developing economies, in particular, are undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization. This involves massive construction, increased manufacturing, and the expansion of infrastructure, all of which are highly energy-intensive. Even with efficiency gains, the sheer scale of this growth drives up overall energy consumption.

- Emerging technologies: The growth of data centers, AI, and other digital technologies is leading to a significant increase in electricity demand.

3. Population Growth:

While efficiency might improve per unit of output, the overall global population continues to grow. More people, even if individually more efficient, will inherently consume more energy in total.

4. Shifting Economic Structures:

- Some economies are shifting from less energy-intensive sectors (like agriculture) to more energy-intensive ones (like manufacturing or specific services).

- Even within industries, while individual processes might become more efficient, the overall scale of production can increase dramatically.

5. Energy Price and Policy Factors:

- Low energy prices: If energy remains relatively inexpensive (due to subsidies or abundant supply), the incentive for significant behavioral changes to reduce consumption might be diminished, even with efficient technologies available.

- Policy limitations: Although many countries have energy efficiency policies, their impact may be offset by other factors that drive demand.

Conclusion: While technological advancements and efficiency measures reduce the energy intensity of specific activities, these gains are often outpaced by the aggregate increase in demand for energy services driven by economic growth, rising living standards, population increases, and the adoption of new, energy-intensive technologies and behaviors. The challenge lies in achieving a proper decoupling of economic growth from energy consumption, and ultimately, from carbon emissions.

Humanity's per capita energy consumption has been steadily increasing with each passing century, a trend that is unlikely to change soon. Therefore, humans of the 26th century will consume far more energy than those of the 21st century.

The authors of After the Spike would probably argue that in 2525, we'll be using a clean energy source (e.g., nuclear fusion), so it'll be irrelevant that our per capita energy consumption increases ten times.

Again, short term, we're going in the wrong direction. However, in a stabilized world, we won't have a problem.

3. Designer babies

The authors of After the Spike never addressed the potential impact that designer babies may have. I coined the term "Homo-enhanced" to address our desire to overcome our biological limitations.

Couples are already using IVF to select the gender and eye color of their babies. Soon, we'll be able to e